How and why farms were different before World War Two

Farms changed dramatically in and after World War Two. This page describes how and why, but concentrates on pre-WW2 farms and what was described as mixed farming. Features are the contributions from individuals who knew such farms personally.

____

By the webmaster based on personal recollections, discussions with others and additional research

The huge Government endeavours to keep Britain fed during World War Two and afterwards meant that farms and farming would never be the same again. This page is about farms before the transformation. Most of it was what was known as 'subsistence farming' and 'mixed farming' - more of which below -which was inefficient and output was low.

Layout of farms before World War Two

Most people in Britain before the 1950s would recognise the features of a farm and farmyard because the countryside was only a short bus ride away from most towns. Double-decker buses gave excellent panoramic views of the fields, and the walks from bus stops took us into fields and through muddy farmyards. Farmers never seemed to mind strangers walking through their fields and farm yards, provided of course that they did no wanton damage. Transmission of farm diseases like foot-and-mouth and salmonella didn't seem to be issues then.

Tap/click for larger, legible images

Bill Hogg who supplied the drawing and gave much useful information, points out that the perspective is not entirely accurate in that the farmyard was wider and the farmhouse larger than shown in the drawing. Nevertheless the drawing gives a good indication of the almost higgledy-piggledy size and shape of the buildings as they grew up in an ad hoc manner as required.

Below the drawing is a map of the same farmyard and farmhouse showing the functions of the various buildings. Both images enlarge on tap/click.

Who owned the farms?

Farms were relatively small, such that in rural areas, there seemed to be a different farm every few miles in any direction. In general, the farmers rented them from fairly wealthy landowners.

Mixed farming and what it entailed

Farming was almost entirely 'mixed' in that, unlike in more recent times, there was no single speciality such as, for example, just dairy farming or just pig farming. Most farms usually had a small herd of cows, a bull, a flock of sheep, a few pigs, chickens and some crops.

The sheep

Counting sheep

contributed by John Boulton

It was general practice to count sheep in units of 20 called scores. One score=20.

Some flocks of sheep were quite large and anyone trying to count them would quickly lose count, but there was a way round this:

Each area of the country had its own way method. On farms in Lincolnshire where I grew up, a shepherd would count up to twenty in the local way and then pick up a small stone and put it in his pocket. At the end of the count, he would just count how many stones he had in this pocket, which told him the number of scores of sheep he had.

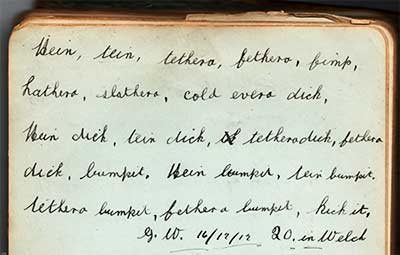

This counting method stems back to the Celtic language with dialects tweaking how it was spoken in different parts of the country. In 1912, George Wright, of Minting, near Horncastle wrote the Lincolnshire way in my grandfather's autograph book. To us today it may looks like nonsense syllables, but apparently it worked well and was chanted like a rhyme.

A way of counting sheep in units of 20. Apparently the writer, George Wright believed it to be Welsh, although, according to John Boulton, the origin was Celtic.

Yan, tan, tethera, pethera, pimp;

Sethera, lethera, hovera, covera, dik;

Yan-a-dik, tan-a-dik, tethera-dik, pethera-dik, bumfit;

Yan-a-bumfit, tan-a-bumfit, tethera-bumfit, pethera-bumfit, figgot.

The cows and the bull

There were usually something like twenty or thirty cows and one bull.

The cows were milked twice a day in the cowshed. They were taken into the cowshed at night and led out to the fields in the daytime. The bull, though, was not allowed in the fields with the cows because he could be dangerous. He had a ring through his nose. He lived inside a barn except for when he was brought out to service a cow. Farmers knew when a cow was ready for servicing because her milk was drying up or it was some time since she calved. The cows were bred for meat as well as for milk.

The pigs

Pigs were kept in a fairly small confined and muddy space called a pigsty. In fact any untidy, dirty human living room was often described somewhat rudely as a 'pigsty'.

I understand that the pigs were not allowed out of their pigstys. I well remember walking past them as a child. Even the pigs were muddy, not that there seemed to be any indication of ill-treatment. I understand that they would eat almost anything, including pig swill.

When the pigs were fat enough, they were taken to market or a butcher for slaughtering.

Sizes of pigs for the slaughter - and the resulting taste

contributed by John Boulton, personal experience

On our family farm, my grandfather used to kill two pigs a year, one just before Christmas and one just after. He wouldn't kill a pig until it reached twenty-score live weight - that's 400 lbs (181 kg). That's really huge. Today pigs are slaughtered between 80 kg and 100 kg. Even the large 100 kg ones tend to be too large for the supermarkets, so are graded out for bacon. That is why pork and bacon have no taste these days.

None of the meat on our huge pigs was wasted: There were pigs fry and sausages for the farmhands as well as a giant pork pie. The remainder was salted down to preserve it. It was my job as a boy to rub the salt into the meat for bacon.

The horses

The farm's horses were the heavy sort who were there for heavy work where there were no petrol driven vehicles.

They were wonderful large and strong animals, bred specially for farm work and they could pull quite heavy loads with comparative ease and respond readily to instructions. They were widely known as 'shire' horses, 'cart' horses or 'work' horses.

The horses' work

contributed by V. John Batten

Probably the hardest work that the farm horses had to do was to pull the heavy reaping machine. Two pairs of horses were employed wherever possible. While one pair worked, the other pair rested in the shade.

The horses were tired and hungry at the end of the working day. They would usually walk at a faster pace homeward bound than they did going to work, because, as they neared the farm their thoughts naturally turned to food and rest.

In fact 'work horse' was a common term in my childhood. If my mother felt that she had been working particularly hard with no help from other people who had been lazing around, she would come into a room and announce, "Here comes the workhorse".

At the end of a gruelling and probably boring time in the fields, the men had to tend to their horses before themselves. The horses lived in stables when not working.

The massive size of farm horses

contributed by Pamela Southin

A farm horse

I remember a lovely farm horse which had furry ankles and an enormous flat back on which I said I could do ballet! I was very young at the time.

The farmers, the farmhands and their families

The farmers who worked these small farms were known as tenant farmers because they rented their farms. They, their families and their farmhands had to work extremely hard for long hours because the mixed farming required so many different and essential tasks.

The farmer's family lived in the farmhouse, while the farmhands and their families lived in cottages some short way away.

| sources | webmaster | contact |

Text and images are copyright

If you can add anything to this page or provide a photo, please contact me.