Monday washdays: the weekly wash/laundry before electric appliances

____

In the past, every item in the wet wash/laundry had to be wound through the mangle to remove the majority of the water, but this still left it damp. How it was then dried depended on the weather because there were no spin driers or tumble driers. This page describes, explains and illustrates how drying the wash was done outdoors in good weather and indoors in bad weather.

____

Extracted from the memoirs of the webmaster's mother (1906-2002) and edited by the webmaster with further research and firsthand contributions from others

It always amazed me how women used to manage on washdays when I was a child in the early 1900s.

There was no running hot water and there were no detergents, washing machines, spin dryers, tumble dryers or rubber gloves. It was just hard physical grind.

Washday - always Monday

Washday was once a week. It was easier to do it on a single day rather than spread throughout the week because so much was involved. It was always on a Monday, and it took the whole day, starting between five and six o'clock in the morning. There was no time for much else, particularly preparing meals. That was why washday was always on a Monday, because the meals could be cold leftovers from the Sunday roast.

Hot water from the copper

Before breakfast, the copper in the scullery was lit to heat water. Filling it took about six bucketfuls, all drawn from the single brass cold water tap over the sink, there being no running hot water.

Galvanised tin bucket, as used for filling a copper. Photographed in Fagans Museum of Welsh Life.

Separating the 'whites' from the 'coloureds'

The whites (sheets, tablecloths and handkerchiefs) and the coloureds were separated out because they had to be treated differently. Once the water in the copper was hot, some of it was bailed out into a wooden tub for the coloureds which were put into it to soak.

Wooden tub

How the 'whites' were washed

The whites were put into the rest of the water in the copper and set to boil with soap and soda added. In those days, these 'whites' were always made of cotton as there were no man-made fabrics which of course would not have stood boiling.

The soap and washing soda

The soap was carbolic household soap, usually made by Sunlight. We lived in a hard water area, so the soda was necessary to prevent the soap producing scum.

Sunlight carbolic soap used with washing soda for the weekly wash before the age of detergents

At last - breakfast

It was while the whites were boiling and the coloureds were being soaked that my mother gave us breakfast.

How the 'coloureds' were washed

After breakfast the coloureds were washed in the wooden tub.

Depending on the wash load, some of the coloureds were washed by forcing them up and down onto a washboard, a corrugated metal or glass sheet in a wooden frame. My mother had to stand to do this in order to get enough pressure to force the clothes onto the ridges in order to get the dirt out, and it was very hard, hot, steamy work.

A washboard used in a sink of hot soapy water or tin bath. Rubbing the washing up and down against the ridges forced out the dirt.

Note from the webmaster

Why wooden tubs

I assume that the wooden tub rather than a tin bath was used for several reasons. Wood would be quieter than tin when the dolly was banged around inside and, being relatively deep, the water was less likely to splash. Also the water would have stayed hotter in a wooden container than a shallower metal one.

Alternatively or additionally the washing was poked and agitated around in the hot soapy water with a wooden contraption called a dolly. There were some quite sophisticated dollies with handles and 'stumpy legs'; but it was quite common just to use a wooden stick.

Wooden dolly used for agitating the water when washing clothes - before the age of washing machines. The handles were held in both hands and swished around.

Rinsing and mangling

The wooden stick or dolly or wooden tongs was used to lift the washing out of the dirty water. Then every item was put through the mangle to get rid of as much dirty water as possible. The mangle and the mangling process have their own page, but it is worth stressing here that mangling was hard work.

The washing had to be rinsed by letting it drop from the mangle into a bath of cold water.

It had to be rinsed and mangled several times.

The women had to be strong to lift sheets and tablecloths in and out of the various baths because wet washing was much heavier than a dry load.

The baths for rinsing were oval galvanised ones, commonly known as 'tin baths'. They came in various sizes, all with handles at each end so that they could be hung up on the wall in the yard outside when not in use.

'Tin baths of various sizes

The blue bag to keep the whites white

The final rinse of the whites was in blue water from a bluebag which was a small muslin cloth tied round a small cube of blue substance and kept in a bowl of water.

Blue bag, Reckitt's Blue, to make the washing look whiter

It was important to be sure that the bag never leaked because otherwise little particles of blue would come out and leave small blue dots on the washing. (The blue bag was also used to dab on bites and stings to ease the pain.)

Another way to keep the whites white

contributed by Anne Jameson, childhood recollection

My mother would put her whites on the line in the frost because, she said, it helped to keep them white. I used to help her shake them vigorously before bringing them in to get rid of the frozen water so that they would dry more quickly.

The blue bag treatment for stings from stinging nettles

contributed by Christine Tolton, formerly Christine Culley

When my friend fell into a patch of stinging nettles, my mother dabbed her skin with Reckitts Blue because it was supposed to soothe the rash!

After the final rinse, as much water as possible had to be removed before the washing was set to dry. Small items were wrung out by hand but most things had to be put through the mangle again.

Laundry starch

The tablecloths were starched in a tin bath.

Starch was bought in a paper pack containing granules, and it had to be made up specially every time it was used, It was first mixed with a little cold water, and then boiling water was quickly poured onto it. If the water was not hot enough, the starch would not thicken, and if the stirring wasn't rapid enough, the starch would go lumpy. The process was rather like making custard or sauce.

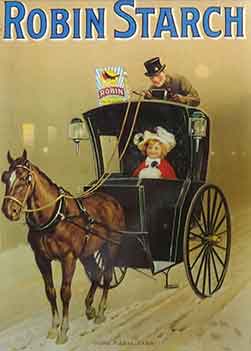

Poster advertising Robin starch. There is a packet of it on the roof of the coach. There were other starches, eg, Reckits and Colemans

Washday lunch (known as dinner)

Women didn't have time to cook on washday. So when we came home from school for dinner (our mid-day meal) we were always given cold meat from the previous day's Sunday roast, served with bubble and squeak made from the left-over vegetables from the Sunday roast. That was why washday was always on a Monday. We ate the meal with mustard pickle that one of us children had to go and buy from the shop at the end of the road. We had to take our own basin. It was sold from large jars and cost 1 or 2 pennies.

Clearing up after the wash

Clearing up had to be fitted in with drying the wash - see separate page - and providing meals.

First of all, the tin baths were put away on hooks on the outside scullery wall or the fence in the back yard outside the scullery door, alongside the mangle.

Tin baths hanging on the outside scullery wall of a small Victorian house

Next my mother scrubbed the scullery floor with a scrubbing brush and a bucket of soapy water. She also scrubbed the copper which she then hearth stoned over. Hearth stone was a kind of stone used in particular for cleaning doorsteps.

Washday tea

When we children came home at the end of the afternoon, tea, as it was called, was simple and the same every day, washdays included: bread and jam or bread and dripping and a slice of cake if any was left from the Sunday baking.

How the work affected women

With no rubber gloves and no labour-saving devices, can you imagine what women's hands must have been like with all this washing!? Smooth hands were a status symbol, showing that a woman had servants to do the washing and cleaning; and ordinary working class women, always tried to hide their red and rough hands when they went out. This was probably the reason for the fashion for elegant, fitting gloves.

Tempers certainly frayed on washdays, and you can understand why. My mother had to do her mother's wash too, as well as her own family's, and this was by no means unusual in families.

The one and only way that the weekly wash was easier in the past

Note from the webmaster

Difficult as washday was, the volume of washing was nowhere near as much as today.

Underwear was certainly washed frequently, but thick top clothes tended have to last just with dirty spots being sponged off.

One sheet from each bed was washed weekly with the last week's top sheet becoming the next week's bottom sheet. (Bedding was sheets and blankets, as duvets were unheard of, and the blankets were washed once a year in good drying weather in the summer.)

| sources | webmaster | contact |

Text and images are copyright

If you can add anything to this page or provide a photo, please contact me.